Spoiler: codes aren’t bureaucracy, they’re coordinates.

With classifications, a model stops being a pretty 3D cloud and turns into a catalogue you can filter, quantify, and exchange without getting lost.

Parameters — Theme: Classification Systems in AEC • Audience: BIM beginners • Goal: understand classification systems and use them properly in Revit and the CDE • Length: ~1,800 words • web: off

Context & problem (why this matters now)

Every project starts with a promise: “this time the data will be tidy.” Then you open the model and learn that “door” is called “door_01_finalissima_v3.” That happens because there’s no map. In Building Information Modeling (BIM – Building Information Modeling) classifications are that map: they tell you what an object is, where it sits, and what it’s for. Without codes, the model stays mute: no reliable schedules, no clean IFC – Industry Foundation Classes exchanges, no COBie – Construction‑Operations Building information exchange the facility manager can actually use. The ISO 19650 series and UNI 11337 remind us that data isn’t accidental: it lives in a CDE – Common Data Environment and comes with clear metadata.

If you understand what to classify (function, system, product, space), you stop asking “where do I put this parameter?” and start asking “how do I reuse this code in quantification, specifications, handover, and operations?” That’s the shift from modeling for drawings to modeling for purposes. The difference between a pretty model and a useful one.

Central idea / concept map (the map is not the territory)

A classification isn’t a sticky label at the end: it’s a perspective. The same building can be read as functions (elements of the works), as systems and products, as work results, as spaces, or even as assets of the organization that will operate it. Each standard lights up a portion of the territory; the trick is to use the right torch at the right moment without blinding the team with a thousand lights. The funnel is this: purpose → table → Revit parameter → output. Respect it, and data flows from the model to IFC/COBie and then to the CDE without drama.

A tiny ASCII sketch so we don’t get lost:

[Purpose] ──> [Table] ──> [Revit Parameter] ──> [Output]

Early cost plan Uniformat / Uniclass EF AssemblyCode / EF_code QTO and costs

MEP coordination Uniclass Ss Ss_code (instance) Views and filters

Specs/procurement MasterFormat / Pr / Omni23 Keynote / Pr_code Specifications

Asset/Facility Uniclass En / SL + COBie En/SL (Rooms) AIM and FMFormats and taxonomies (no yawns)

Uniformat (UniFormat II) looks at what it does: the taxonomy for elements of the works (A Substructure, B Shell, C Interiors, D Services…). It’s the lens you want when you need to estimate and compare options without drowning in detail.

Uniclass 2015 is a collection of facet tables: Co (Complexes), En (Entities), SL (Spaces/Locations), EF (Elements/Functions), Ss (Systems), Pr (Products). It natively speaks the language of BIM and interoperability. It demands discipline, but pays back: with Ss you filter building services systems, with Pr you differentiate products, with SL you anchor spaces.

MasterFormat and OmniClass bring order to how we describe work results and products in specifications. In the Anglo‑American world they’re the de‑facto standard; in Italy they often live alongside DEI/regional price lists.

Then there’s the home base: UNI 11337 (information management, roles, processes, coding criteria) and ISO 19650 (information processes, requirements, LoIN – Level of Information Need). They’re not there to “freeze” you, but to provide rails your data can run on.

Key idea: classifying ≠ “sticking a random code”. It’s choosing a view that serves a purpose and fixing it into stable parameters. Once you get this, you stop asking “how much LOD?” and start asking “LoIN for what?”.

Revit: the right hooks (and what to avoid)

Revit already gives you a few handles. Assembly Code is perfect for Uniformat in early phases. OmniClass Number helps when you work with OmniClass or need a neat parking space for other taxonomies. Keynote is the natural hook to specifications. Mark/Type Mark aren’t classifications, but they’ll save your life for schedules and QA. The rest you do with Shared Parameters: Uniclass_EF, Uniclass_Ss, Uniclass_Pr for elements and families, Uniclass_En and Uniclass_SL for entities and rooms.

One rule that never betrays you: put it at instance level where context matters (rooms and spaces, installed systems), and at type level where the class doesn’t change (doors, diffusers, fixtures). Keep parameter names short and consistent, and use QA schedules with a “Is Empty?” column to expose the gaps. Don’t fall in love with a single standard: in Italy, dual coding (Uniclass for interoperability, Codice_Listino for bills of quantities) is often the only way to avoid acrobatic copy‑pasting between Revit and Excel.

From the model to the CDE: the social life of data

Data doesn’t live only inside Revit. When you export to IFC, remember Classification Reference exists: if you mapped EF/Ss/Pr correctly, the codes will travel. In COBie those codes attach to Type and Component and become real filters for whoever will operate the asset. In the CDE – Common Data Environment (think Autodesk Construction Cloud with Docs and BIM Collaborate) files aren’t “deposited”: they are information containers with Status, Revision, and yes, Classification. This is where coherence really pays: if a container is marked S1 – For coordination and carries revision P01, nobody will “accidentally” use the wrong PDF or an RVT that hasn’t been shared.

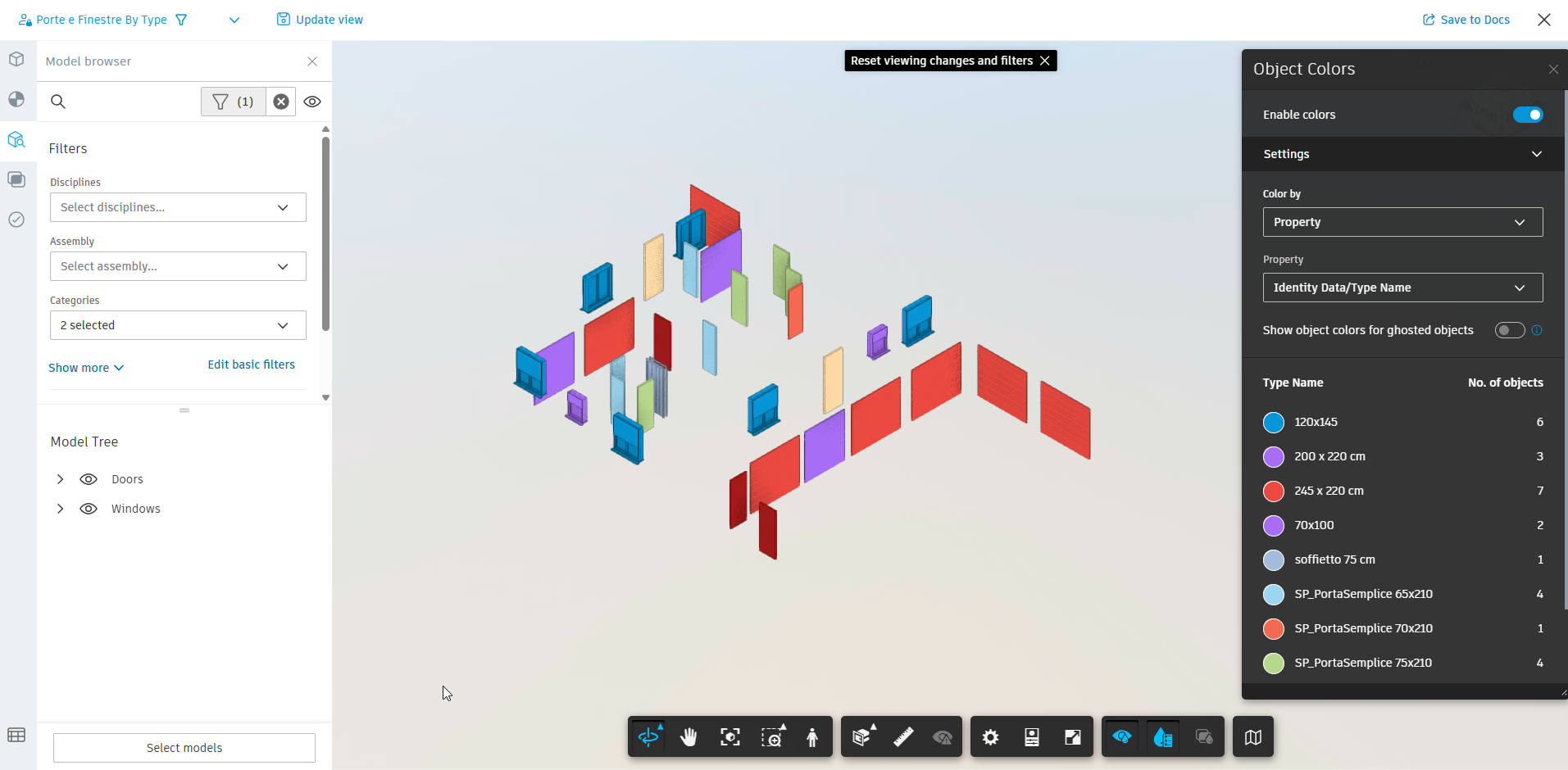

And if you want to count without Revit? The surprise is Model Coordination: it isn’t an online schedule, but it does a missing trick. Open the model in the browser, filter by properties (category, discipline, custom parameters), switch on Object Colors and choose Color by → Property (type, Fire Rating, Uniclass…). The legend returns how many objects per value. Two clicks and you have “all EI60 doors,” coloured and counted. Save the view and share it in Docs for those who never open Revit: visual QA, fast, democratic.

Use case A — “BEP for a School: Uniclass as lingua franca”

Picture a new secondary school. The client asks for clear schedules, clean IFCs, and MEP coordination without drama. In the BEP – BIM Execution Plan (PGI in Italian) you decide the language will be Uniclass: En/SL for campus, building and classrooms; EF for architectural and structural elements; Ss for services; Pr for recurring products (doors, luminaires, terminals). In Revit, parameters are ready in the template; in QA schedules the gaps show up immediately.

Every week a pilot: you export IFC, check the Classification References, generate a minimal COBie with codes on Type. Meanwhile in Model Coordination you save three views: “Classrooms by SL,” “Systems by Ss,” “Critical products by Pr.” People who only need to review don’t open Revit: they enter, filter, count, comment. Result? Repeatable deliveries, traceability in the CDE, zero “temporary” side‑spreadsheets that will contradict themselves sooner or later.

Use case B — “Uniformat + Keynote for a Hospital: decide fast”

Hospital extension, a decision in four weeks. Here you need speed. Put Uniformat on Assembly Code and think in blocks: shell, interiors, services. Build cost‑centric schedules that speak clearly even to those who don’t breathe BIM. The few critical voices are tied to Keynote (MasterFormat or price list) so you don’t lose them later on.

When the project enters detailed design, you don’t blow up what you built: you introduce Uniclass (Pr/Ss where you need granularity) and keep using Uniformat codes for option comparison. It’s a gentle transition: no epic recoding, no double truths. Repeatability without rigidity.

Common mistakes → antidotes

First mistake: mixing standards without a purpose. Uniformat today, fantasy codes tomorrow, MasterFormat the day after “just because.” Antidote: tie each table to an objective (estimate, coordination, tender, operations) and write it down in the BEP.

Second mistake: free‑text parameters. In two months you’ll have three variants of the same code. Antidote: Shared Parameters with controlled lists, QA schedules with “Is Empty?” and colour overrides in views for unclassified elements.

Third mistake: codes only in the model and not in the CDE. Then nobody finds the right version. Antidote: in Docs use Status/Revision/Classification as information‑container metadata. The CDE isn’t a fancy Dropbox: it’s the project’s ledger.

Fourth mistake: confusing LOD with LoIN – Level of Information Need. There’s no magic LOD that saves everything. Antidote: ask “what purpose?” and define LoIN (geometry + alphanumeric + documents) in the EIR – Exchange Information Requirements; then actually verify it at delivery.

Helpful counter‑example: Uniclass everywhere, always. In a concept sprint it can become a noose. Antidote: start with Uniformat/EF to line up costs, then unfold Ss/Pr where needed.

From the CDE to Business Intelligence (let the numbers talk)

Quality can’t be eyeballed. If you export schedules and/or run a property harvest from models published in ACC, in half an hour you have a dataset that tells the story of the project: how many doors have Fire Rating filled in, how many elements carry the Uniclass code, how many spaces are missing SL. In Power BI or Tableau you can build a dashboard a Project Manager gets at a glance: a widget for “% of elements with a code,” a chart of EI doors per floor, a trend of completion by milestone, a matrix of category × LoIN.

Note: The Milan‑based training and consulting firm Forma Mentis*, with whom I often collaborate, has just completed the course* “Power BI(M) – Fundamentals of Business Intelligence.” They’ll likely run a second edition soon, so keep an eye on their website.

Intelligence”** (Forma Mentis). Two instant tips: a star schema (Facts = elements; Dimensions = categories, codes, levels, phases) and a tiny DAX measure to count elements without a code. Publish the report next to the models in Docs. This way the construction manager won’t ask “send me the Excel”: they open the dashboard and see the status in real time.

How to start tomorrow (practical to‑do)

Choose your strategy and write it into the BEP: Uniformat/EF for concept and costs; Uniclass Ss/Pr for coordination and tenders; En/SL + COBie for the AIM – Asset Information Model. Prepare a Shared Parameters schema with short names (EF_code, Ss_code, Pr_code, En_code, SL_code, Codice_Listino) and seed your most used families. Train the CDE: in Docs enable Status/Revision/Classification and use coherent naming. Run a pilot: 10 classified families, a test IFC, a Model Coordination view coloured by Property, and a mini Power BI dashboard highlighting where codes are missing. From there, short, steady iterations.

Note/Disclaimer (standards and limits)

This text follows the ISO 19650 and UNI 11337 framework: set upstream requirements (OIR – Organizational Information Requirements, AIR – Asset Information Requirements, PIR – Project Information Requirements, EIR – Exchange Information Requirements), agree on LoIN, govern data in the CDE, and think open (IFC, COBie) from day one. National annexes may specify naming and container IDs: align with them, but don’t lose sight of the prime principle — documented coherence.

In a nutshell: choose the right table for the purpose, hook the right parameters in Revit, use Model Coordination for fast checks and counts, and let a BI dashboard make the data speak. That’s the difference between modeling and managing information.